Career Highlights

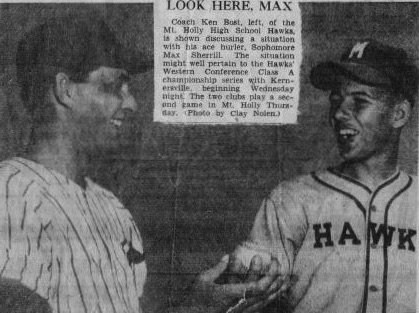

Led the Hawks to post season success with 12-2 record in ’54 and 8-2 in ‘55

Batted cleanup, and played right field when not pitching for the Hawks

Played minor league baseball for 6 seasons

Later worked for Eastern Airlines

Was an avid golfer until his death in 1998

Max Sherrill

On a 1940s summer day, two young boys emerged simultaneously from their company-built homes in the steam plant neighborhood where the Catawba River carves a horseshoe plateau, and stepped tentatively into the gravel street to form a friendship from which they would never back away.

“I walked out my back door into my backyard, which faced his front yard, and we looked at one another, and slowly moved toward one another as 6-year-olds would do, and when I got to my side of the road, I wouldn’t cross. And when he got to his side, he wouldn’t cross,” said Don Killian, who can vividly recall the moment of 72 years ago. “We looked at each other, and later we’d argue about how long we just stared at each other. Then one of us said, ‘How old are you?’ and the other said, ‘Well, how old are you?’ and that started it right there. “We continued to talk, and moved toward the center of the road, sizing one another up. Before that morning was over, we set over in his yard and talked and talked… We just hit it off. He was so friendly.”

The other child was Max Sherrill, and he was a bit bigger, and for some reason Killian decided to call him ‘Goot.’ Mr. Sherrill called Killian ‘Little’un.’ And like the friendship, the nicknames also never went away.

Mr. Sherrill would grow up to know success in baseball – in high school, in college, and in the late nights and long bus rides that defined the minor leagues. Killian became an educator in the subjects of cognitive psychology and sociology. But before they grew up to become men, they had the time of their lives.

“Our personalities complemented each other. We were just joined at the hip, I guess you could say. He was always kidding around, and I was more serious about things,” Killian said. “I always wished I could be as jolly as him. He’d say, ‘Little’un, you’re too serious about your stuff.’”

The boys’ daddies worked in Duke Power’s Riverbend machine shop – together – and the children passed time with games. “We’d play too much and didn’t work enough. We played every sport you could mention, and we’d create our own seasons,” Killian said. “We’d have baseball season, then tag football season, then marbles season – they’d all last about a month – then rubber gun season.”

A rubber gun was built from a square board, a clothespin and rubber band. Baseball season got more creative. “We’d hit rocks with a broom handle. We’d cut the broomsticks the length of the bat, and pick up a rock to hit the size of a pecan. You’d be amazed what that does for your eyesight,” Killian said.

Early thrills produced older skills.

Baseball remained the constant, and Mr. Sherrill pitched while Killian played short stop in junior high and high school, then on American Legion teams. They played for Mount Holly High, where Mr. Sherrill helped lead the team to the 1954 and 1955 Little Ten Conference titles, with a 29-4 record those two years. That ’54 team, Killian recalled, was Class A state runners-up. The Sherrill family moved to Stanley his senior year, which put the best friends in different jerseys for the first time.

“Max was torn. But when we played baseball against each other, he’d say before the game, ‘Now, I’m gonna bring you some heat from time to time, but you and I both know you’ll get it right,’” Killian said. “I could tell when I was gonna get his fastball. I knew what was coming.”

Killian went on to play four years at Davidson, while Mr. Sherrill joined Pfeiffer for one year before the call came from the Chicago Cubs.

His senior year in Stanley, Mr. Sherrill had met a girl, Linda Thompson, daughter of well-known coach Dick Thompson, whose household had strict rules about boys. “I always knew who he was. We met when he was a senior, and I couldn’t date till I was 16, but Max was not scared (of Mr. Thompson),” Linda Sherrill said. “So, on September 25, 1955, when Mount Holly was playing Cherryville, Daddy told me, ‘Well, I guess I’ll let you go with him this time. Nothing will become of it.’ And look what happened.”

They were married for 22 years, and had three children, Anne, Matthew and Mike, who died in 2012 from cancer.

When the Cubs called, the couple went to Pulaski, Virginia, where Mr. Sherrill, a 6-foot-3, 220-pound right-hander, went 2-10 with a 5.95 ERA in 62 inning. The following year, in Paris, Illinois, with the Class D Paris Lakers of the Midwest League he went 10-12 with a .420 ERA and 164 strike-outs.

After three seasons in the Cubs organization, the Sherrills moved on to Class B ball with the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox clubs in Raleigh and Wilson, N.C.

“Our days and nights were mixed up, so we’d sleep during the day and then after the games, we’d go out and get pizza,” Mrs. Sherrill said. “We had a wonderful time. We’d go on road trips to Morehead City and the beach, and I have such good memories of that time.”

Mr. Sherrill played six seasons in the minors, ending in 1962. He had an overall winning record his three seasons in B ball, at 17-12, with 20 starts in the 71 games he took the mound.

When faced with the choice of relocating to Bismark, North Dakota, for Class A, Mr. Sherrill said no. Too cold, too far. He came home to Mount Holly.

“He worked for Eastern Airlines. One day on a whim, he rode over there and they hired him on the spot,” Linda Sherrill said. “He did ramp service. He held the wands to show the planes how to get in and out, and he survived all the layoffs. He’d bring home these little models for the boys, like real planes.”

Mr. Sherrill died in 1998 after a battle with diabetes. The couple had divorced in 1984.

The Mount Holly Hall of Fame induction, Linda Sherrill said, would have pleased him.

“I was tickled to death, when I heard,” she said. “I thought that one year in Stanley would have made a difference, but his whole life was in Mount Holly. That’s where his best playing days were.”

“He was a cut-up but he was competitive. He encouraged you, he pumped you up,” Killian said. “He’d say, ‘Little’un, you can hit this clown!’ He kept us loose. Looking back … I could not have asked for a better teammate.”